Could the Flames sustain their lopsided ice-time distribution during a deep playoff run?

By Craig Petter

3 years agoOne major storyline from the Calgary Flames’ Game 1 Qualifying Round victory against the Winnipeg Jets concerned their fourth-liners’ ice-time. Seven penalties issued over the course of the game translated to 12 and 11 shorthanded shifts for Derek Ryan and Tobias Rieder respectively. Each of them logged nearly six minutes of ice-time on the penalty kill alone.

Come the Flames’ loss in Game 2 though, the discourse on the fourth-line shifted. Folks online noted that Ryan, Rieder, and heavyweight Zac Rinaldo barely skated all game—Ryan had 15 total shifts (all situations), Rieder registered 14, and Rinaldo posted a pitiful six. Without the boost guaranteed by their PK usage, Rieder and Ryan were buried in the backseat.

And the stats from Game 3 only amplify the fact that the Flames deployed their top three lines to unparalleled degrees during the series against the Jets. Ryan, Rieder and an unscratched Mark Jankowski failed to crack 10 minutes of even-strength ice-time, while the next lowest forward was third-line centre Sam Bennett who boasted nearly 13.

So, the Flames adopted a strategy against the Jets that heavily relied on their top nine forwards and somewhat neglected their bottom three at even-strength. And it worked. The Flames outplayed the Jets, cruised through the series and slotted themselves a playoff berth.

But the disparities in ice-time that won them the series raises a certain question—does playoff success foremost entail outplaying your opponent or outlasting your opponent? Three to four games of grueling and strenuous high-octane hockey a week for up to two months must take a physical toll at some point, right? What comes first for Cup contenders then—skill or spirit? Gifts or grit? Pure ability or prolonged resiliency?

In other words, for how long can nine guys carry the brunt of a workload designed for 12?

There are valid reasons for the Flames to stay the current course, but some clashing figures and philosophies veer towards upping the fourth-liners’ even-strength ice-time. So let’s set the table, sample both dishes and debate our favourite course in the comments below.

Possibility #1: Circulate the 12 a bit more

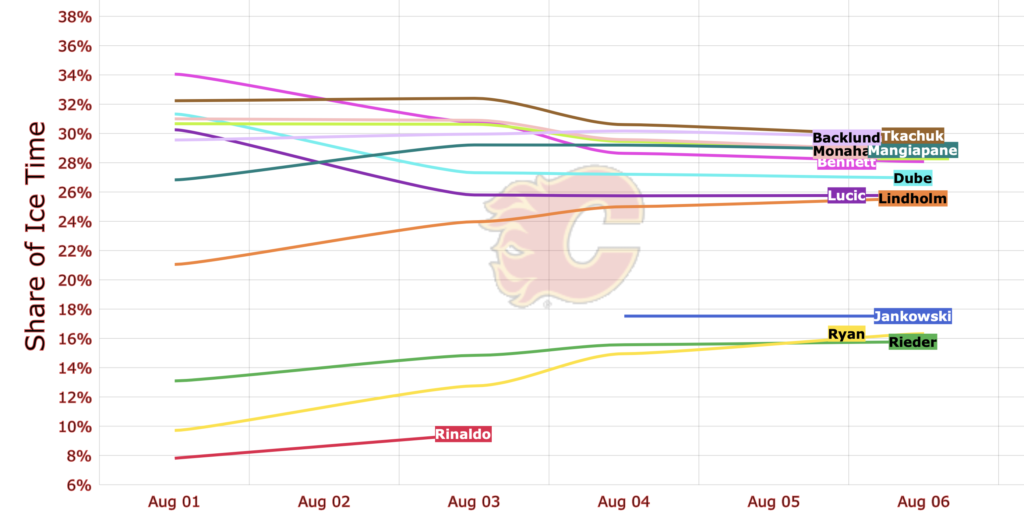

The following graph (courtesy of MoneyPuck) illustrates just how fat the gap and steep the fall in even-strength ice-time have been between the Flames’ top three lines and bottom unit so far these playoffs. It pinpoints and traces what percentage of even-strength ice-time per 60 minutes of hockey each individual Flames forward has enjoyed compared to the rest of the team.

See the disparity? The top three lines jumble together at the apex, a gulf swells beneath them and the fourth-liners crawl down in the trenches. The difference between the highest forward’s share of even-strength ice-time so far (a throne occupied by Matthew Tkachuk, by the way) and the lowest forward’s slice is a 14.1% spread.

Now, how does the even-strength ice-time share graph appear for teams that ran the whole gauntlet and eventually, finally, at long last won the Stanley Cup?

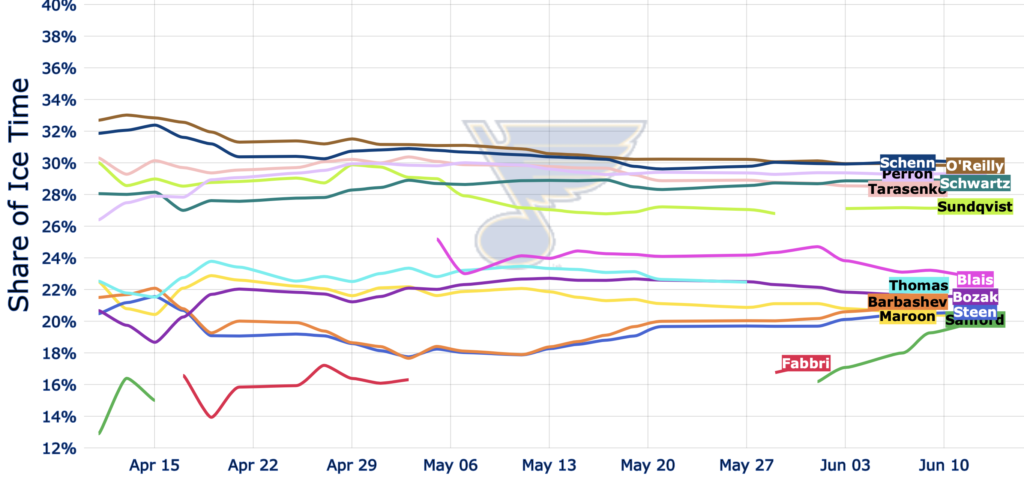

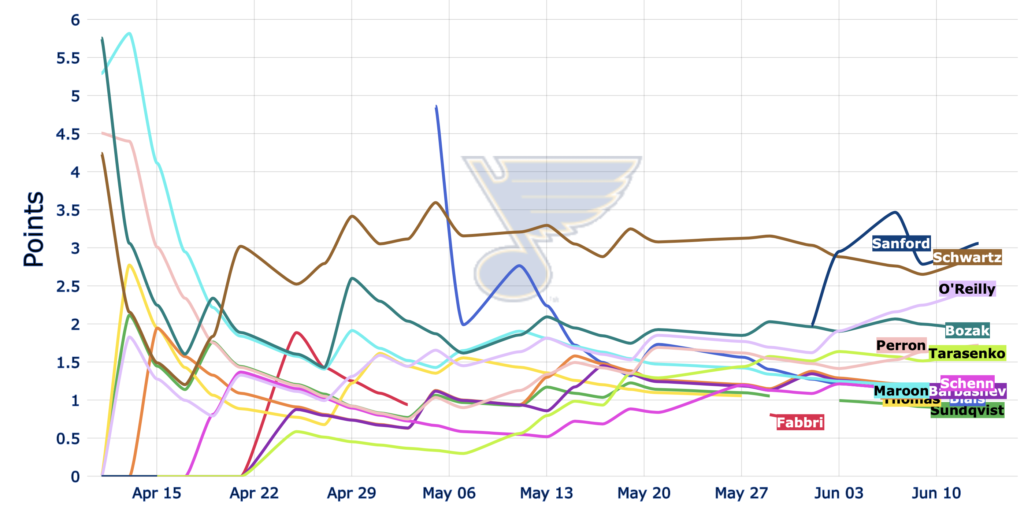

2019 St. Louis Blues (MoneyPuck)

Thinner gap, more gradual fall. The top six record more minutes than the bottom six, but here we see two workloads borne by six guys each, instead of one chunk hoisted by the top nine and the crumbs picked up by the bottom three. And the contrast between the workloads is dimmer—the total range of ice-time shares is only a 9.9% difference between the stars and the grinders.

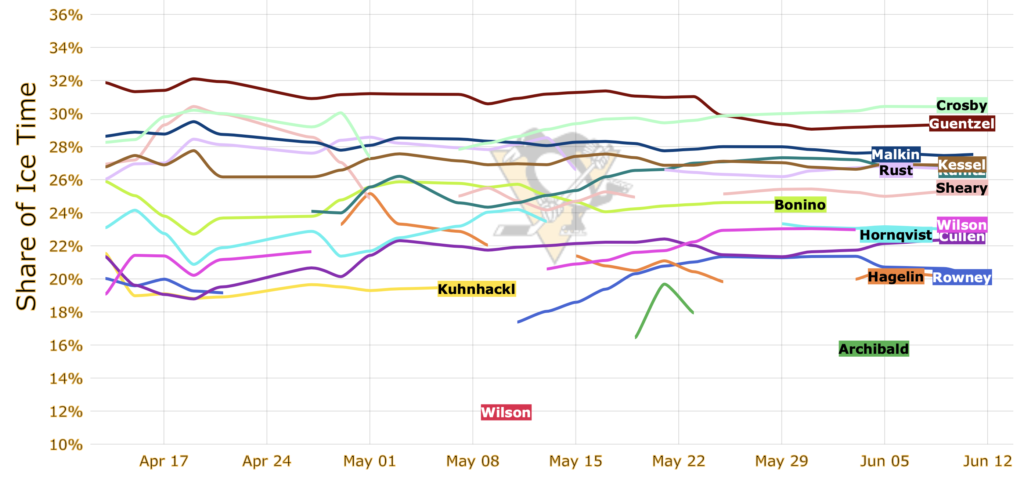

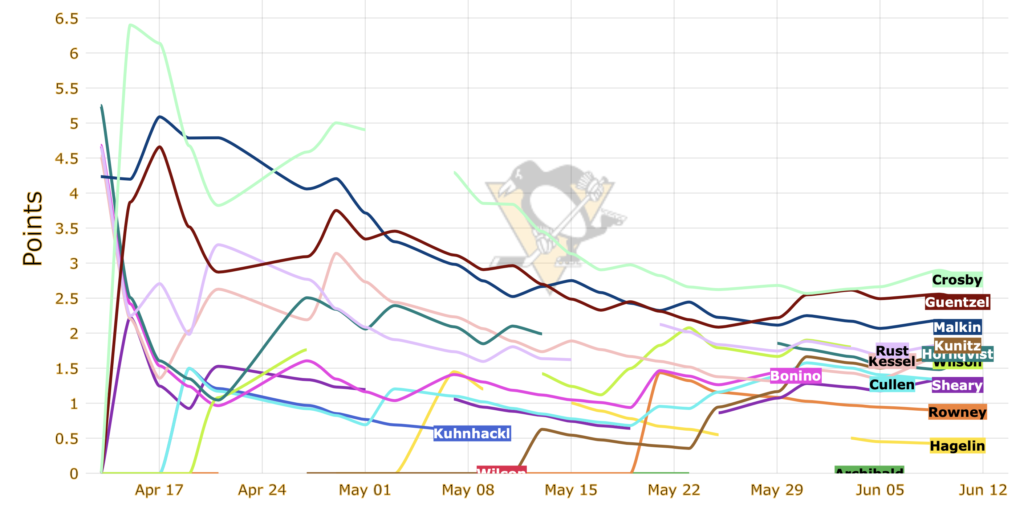

2017 Pittsburgh Penguins (MoneyPuck)

No major gaps at the ends of the lines equal a much more balanced distribution. In that year’s cup final, Bryan Rust played on Sidney Crosby’s wing and Conor Sheary suited up as a fourth-liner, but their shares differed by only 1.4% The total height of the percentage-of-ice-time tide measured from crest to trough is a mere 10.4% difference, too.

Ultimately, Stanley Cup winners tend to roll all four lines at even-strength. Of course, discrepancies between the top lines and bottom lines exist, but they pale in comparison to those practiced by the Flames against the Jets. And the logic checks out. Cycling through the whole lineup at even-strength frees up the energy superstars need to channel during power plays, the final minutes of a nail-biter, etc. The Stanley Cup Playoffs are a marathon, not a sprint, and these teams not only understood but epitomized the cliché.

Possibility #2: Keep emphasizing the nine

But before you can even dream of pushing through to the later rounds of the Playoffs, you need to win the series at hand. NHL players regurgitate the tired old adage “take it one game at a time” for a reason—accumulating wins is how you advance and win the Cup. Spreading out ice-time among four lines during the first round solely to prepare for the Final would be absurd, deluded. The strategy that maximizes your chance to win that night is never the wrong choice. And as the Flames proved against the Jets, that means limiting their fourth line at even-strength.

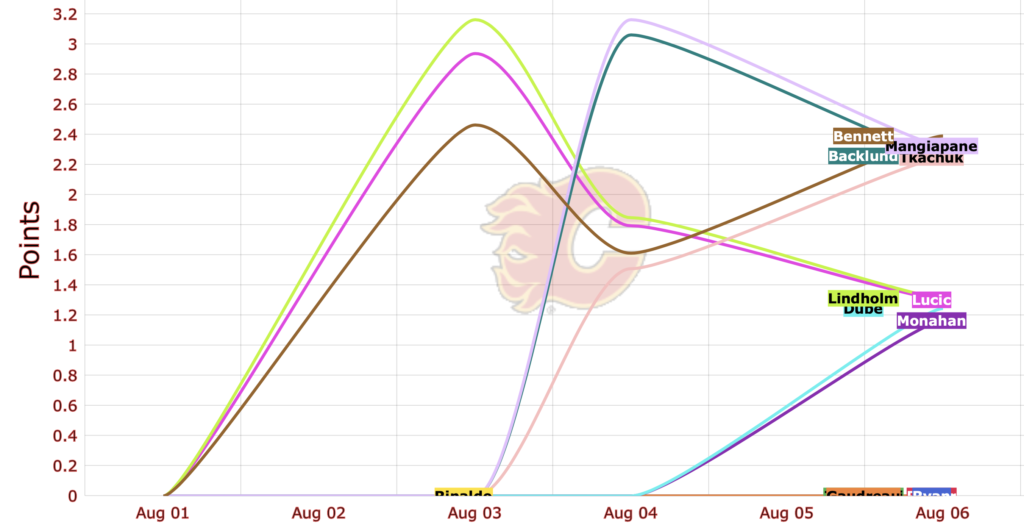

Justifications abound for why the Flames showcased their top three lines so singularly and so often. First of all, the Flames’ fourth line simply does not produce. Top-heavy scoring defines the Flames’ forward corps, for better or for worse—look no further than every player’s even-strength points per 60 in the Qualifying Round (courtesy of MoneyPuck).

The smudges straddling the zero there? Ryan, Rieder, Jankowski, Rinaldo (and Gaudreau, a power play specialist so far, I guess). After 60 minutes’ worth of shifts, the fourth line is not even slated to notch a single point at even-strength at their current rate.

And although the Stanley Cup winners mentioned above supplied their respective fourth lines with weightier slabs of ice-time, it must be noted that those players could actually score even-strength goals on occasion, too. None of the fourth-liners dressing for these squads stagnated at zero points per 60, meaning it takes those guys way fewer shifts to score than the Flames’ fourth-liners.

2019 St. Louis Blues (MoneyPuck)

No smudges straddling the zero, right?

2017 Pittsburgh Penguins (MoneyPuck)

Only two players stalled at zero, both of whom played only four games during the entire playoff run.

So one can conclude that these teams swung the gates open for their fourth-liners as often as they did because, at least a fraction of the time, they expected them to score at even-strength. The Flames have not this luxury. So why on earth would they pinch ice-time away from the guys who generate the goals that win the games? The risk (of losing the games at hand and getting eliminated early) far outweighs the theoretical reward (of conserved energy for a deeper run).

Finally, the Flames’ third line has just been so dynamite and versatile already. Not only did Bennett, Milan Lucic, and Dillon Dube shine on the scoresheet this past week, but together they slam more bodies and spark more fires than the fourth line could ever imagine. On most NHL teams, the fourth line consists of the shakers and movers. Coaches expect their bottom guys to plunge into the corners, slug out battles, hunker down defensively, play the grimy game. Ryan and Rieder and Jankowski could never accomplish this the way Bennett and Lucic do.

So, if the third line provides the tertiary scoring and frenzied physicality customary to fourth lines, why play the latter more than the bare minimum?

What does the C of Red think?

On the one hand, duh, you need to play your best players every night if you want to win. But condensing your lineup every game for up to two months could exhaust your core down the road.

Past cup winners suggest that incorporating all four lines at even-strength unlocks long-term success. But these teams’ bottom trios actually scored at modest, maintained rates.

After sifting through both arguments, we ask again: can the Flames sustain the recent pattern that overtly emphasizes just three forward lines? Should they?

You tell us.

Recent articles from Craig Petter