The Rise and Fall of Darryl Sutter – Part 6, The Decline

By Kent Wilson

13 years ago

Empowered by his initial success and emboldened by the installment of friends and family throughout the organization, Sutter was free to indulge his very singular habits and pursue his very singular vision during his reign as the Flames general manager. The unlikely 2003-04 post-season success and the 103 point season the following year cemented the Flames "contender" status in the mind of the team’s manager, augmenting expectations in town and around the league as well.

The overarching focus of the club became one of the immediate future as a result, with each first-round exit and each failed season only increasing the apparent urgency to make-good the season following. By the end, Darryl was caught in a sort of gambler’s dilemma where his previous actions and investments left him with little option but to continue to throw good money after bad in a vain attempt to bring his vision of another deep playoff run to fruition.

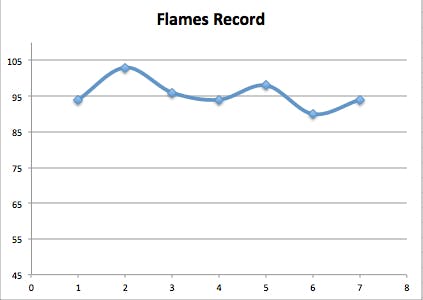

Despite two straight years out of the playoffs, the term "decline" is something of a misnomer when talking about the Flames and Sutter, at least when it comes to regular season outcomes. Calgary was actually one of the more consistent clubs in the league during his tenure, frequently falling between 98 and 94 points per year.

There’s a soft downward trend there (mostly due to to the aberrant 103-point effort in his second season) but it’s nominal. By and large, the Flames were a solid, 95-point team under Sutter; frequently competitive, always in the conversation for a playoff spot. This moderate rate of success is somewhat laudable and at the very least worthy of faint praise, even in the wake of the Sutter’s inevitable ouster. Calgary never completely fell completely out of contention under Darryl, nor was the franchise or fanbase ever forced to suffer through the indignity of a Oilers-style fall from grace and subsequent rebuild (now entering it’s fifth year!). Sutter, with his general obstinancy and ill-temper towards failure, ensured the club would never be debased in that fashion while he was at it’s helm. That’s certainly not a claim some other managers in the league can make.

Spending and Marginal Efficiency

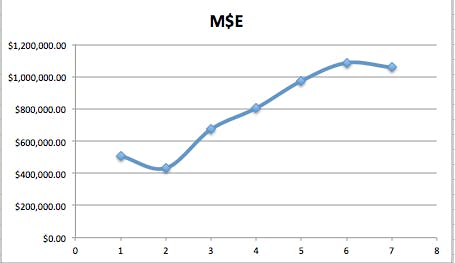

With the above in mind, Sutter’s decline isn’t obvious in the team’s regular season success. His managerial excesses and missteps rear their ugly head when the price of the Flames apparent consistency is considered and weighted accordingly. While Sutter managed to keep the club in the playoff conversation year-after-year, he did so by investing more and more of the organizations dollars, cap space and futures to do so.

In a article entitled Darryl Sutter – Decidedly Average, Derek Zona employs the concept of marginal cap efficiency to grade the various NHL GM’s. Defined as "the number of points per million dollars in salary cap spent over the league minimum salary", MCE is a metric for how well or poorly a general manager is spending his cap space. It’s a crude but meaningful metric since assembling a roster in a capped environment is essential a contest of efficiency – the managers who can best squeeze the most value out of their cap hits will be the most succesful at creating quality rosters.

As hinted by the title, Zona found that Sutter’s efforts between 2003 and 2010 fell right in the middle of the pack in the NHL (1.99 points/MM) over that span.

Averaging the performance over his tenure doesn’t give one the true picture of Sutter’s increasing intemperance over the years, however:

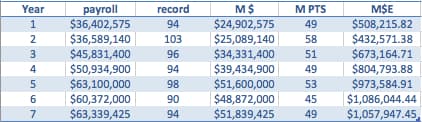

The table and graph show Sutter’s marginal spending (meaning dollars spent above the theoretical minimum-salary team of $11,500,000) and the club’s marginal points per season (points above a theoretical replacement level of 45). Of course, as this is an efficiency rating, the smaller the amount, the better. For the purposes of this investigation, I chose to use actual roster dollars spent rather than simple cap dollars since that seemed to be a more honest way to look at how Sutter was using his resources.

As you can see, the Flames were extremely efficient in Sutter’s first couple of seasons. The cost of the Calgary’s marginal success rapidly increased thereafter, however, with the price of a 95-point team more than doubling over the course of seven seasons.

There are various reasons for this steep acceleration, some of them external and apart from Sutter’s management. Both the Flames budget and the league-wide salary cap increased over the same period, for instance, simultaneously boosting the price of UFA’s and increasing the amount Darryl had available to spend. Some degree of growing inefficiency was probably inevtiable.

Another primary cause of the steep climb upwards, however, was the fact that many of Sutter’s core players were initially underpaid relative to their contributions. Robyn Regehr ($1.95M), Miikka Kiprusoff ($3.33M) and Daymond Langkow ($2.442M) were high value contracts given their cap hits. Add in other decent bargains in the early years (Conroy at $2.546M, Huselius $1.4M and Dion Phaneuf at $.785M) and you have an org paying middling rates for top-notch contributions at the high-end of it’s roster.

Some of these deals Sutter acquired or negotiated himself. Others he inherited. After the Flames early success, the question hanging over the organization was whether Sutter would be able to retain all of the club’s major contributors given their performance and pending unrestricted free agency. Years of a lackluster budget and a weak Canadian dollar had conditioned Calgary fans to expect the worst when it came to paying stars to stick around.

But retain them he did. Iginla re-upped at his previous rate, but Regehr ($4.05M), Langkow ($4.5M), Kipper ($5.833M) and eventually Phaneuf ($6.5M) all got substantial raises. Sutter’s ability to re-sign the Flames big guns was at once a blessing and a curse – a blessing because of the stability and prestige bestowed on the organization thanks to notable stars sticking around. It ensured the Flames ongoing competitiveness and made the club a more attractive destination for free agents.

Ini contrast, it was a curse because paying market-values for your big names eventually becomes untenable in a capped NHL. As the Flames have experienced recently, cap-space and wiggle room become fairly tight when no one at the top-end is outperforming his cap hit. In addition, the new, more expensive contracts to the big boys were almost to a man "legacy deals", rewarding each player for a peak that had already passed, carrying them into the twilight of their career. This season, for instance, the average age of "the big four" (Kipper, Iginla, Regehr and Langkow) was 33-years old. Next year, it will be 34. Their combined cap hit will be just north of $21M.

The lone exception, of course, was Dion Phaneuf. Unfortunately, the success that made him such a bargain as a rookie guaranteed a gross overpayment once he became a restricted free agent. Dion went from one of the best contracts on the club to one of the worst inside a single summer. The fruits of the Phaneuf deal have soured, but the trade was next to inexorable once he signed his name to that contract.

As a result, the core has collectively gotten older and more expensive as the years have passed. They went from bargains to market-priced and are now passing into "poor value" territory.

Replenishing the Core and Spending the Future

The retention of an aging and expensive core was merely one facet of Sutter’s budgetary inflation over the years. As Zona observes in the above linked article:

One reason for this performance might be Sutter’s tendency to trade away draft picks and young talent for veterans and his penchant for signing unrestricted free agents to fill the roster. Salary Cap dollars are saved in entry level deals, and to a lesser extent, on most restricted free agent contracts.

The Flames inability to draft high-end players is well documented. The last legitimate, top-six forward picked and groomed by the franchise was probably Cory Stillman. Under Sutter, Calgary’s drafting continued to be worse than mediocre. In his thorough investigation of the organization’s draft performance last summer, Ryan Lambert showed how the Flames lag well behind the league average in terms of games played and points earned by draftees between 2003 and 2009. In fact, the one player propping up all of the Flames totals in those two categories was Phaneuf – and he is no longer part of the club. Other main contributors, Dustin Boyd and Brandon Prust, were also jettisoned.

As discussed in part 5, Sutter defaulted to experience over youth in general. In part, because vets are a safer bet, in part because the plan never wavered from "win now" (meaning suffering through a youngsters first few, mistake laden seasons was frowned upon) and in part because of the lackluster performance of his scouting department. With so few youngsters available to step in and provide value immediately, Darryl turned to free agents and trades to plug roster holes and supplement the core. This caused him to not only invest more and more cap dollars, but also an increasing number of the club’s future assets as well.

Since 2005, Sutter has traded 2 first round picks, 6 second round picks, 3 third round picks, 2 fourth round picks, 1 fifth round pick, and 1 seventh round pick. He’s traded for 1 first round pick, 2 second round picks, 2 third round picks, 2 fourth round picks, 1 fifth round pick, and 1 seventh round pick. His net loss in five years has been 1 first round pick, 4 second round picks, and 1 third round pick.

That’s Derek Zona again from the same article. In fairness, some of Sutter’s trades involving picks netted the team useful players. Rene Bourque was had for a second rounder, for example. He also frequently attempted to re-stock the futures cupboard, trading down in the first round for multiple later picks when at all possible.

The net result was nevertheless a general lack of draft picks (particularly inside the first two rounds), making the job of acquiring high-end talent all the more difficult for a scouting team that had struggled with such for years at the best of times. Consistently finishing around the middle of the pack didn’t help the situation either – the Flames first choice inside the top-15 under Sutter would have been last summer, for instance, had the pick not been traded for Olli Jokinen.

Darryl’s penchant for trading the future for present gains has been dubbed "deficit spending" by Feaster since he took over in Calgary and it’s an issue that still haunts the Flames in the wake of Sutter’s departure. Although the club has missed the post-season for two years running, it’s likely they will finish with just a single pick inside the top-60 across both drafts – this coming June’s first rounder. Sutter’s inability to internally replenish the club’s talent stock therefore became a sort of hideous feedback loop where futures were spent to assuage the lack of quality prospects, ad infinitum.

Growing Inefficiency and Irrationality

The twin vices of an aging, expensive core and a lack of cheap youth combined to compress the organization’s cap space slowly but surely, more and more, year after year. The final few brush strokes that painted Sutter and the team into it’s current corner was his series of wildly bad bets near the end of his reign. With Iginla et al. drifting away from their peaks, Sutter seemed to become more earnest and desperate in his attempts to push the team over the top. The riverboat gambling essentially began with the acquisition of Olli Jokinen at the trade deadline in 2009. Sutter moved the Flames aformentioned first round pick, Brandon Prust (the first time) and the much cheaper Matthew Lombardi. The move was mostly celebrated, but the truth is it was a fairly bad bet even without the benefit of hindsight.

Jokinen’s reputation was inflated thanks to years of big numbers garnered through soft circumstances in what was the worst division in hockey at the time. He was a power-play forward and a guy who could score on third-liners. He was never the mythical "first line center" the Flames were so desperate to pair with Iginla.

As such, the Jokinen gambit failed. His acquisition didn’t improve the club (just the opposite) added another pricey contract to the books and cost the team a younger, cheaper player and a first round pick. Jokinen wasn’t Sutter’s only mistake over the years, but it stands as perhaps the first true footfall on the path to his demise. With the team faltering in 2010, Jokinen (and Brandon Prust again) were later famously traded for pending UFA Chris Higgins and the boat anchor that is Ales Kotalik. Dion Phaneuf and Keith Aulie were dealt for a collection of middling talent out of Toronto. Admist disappoint and panic, Sutter was basically doubling-down on previous mistakes, trading bad bets for different bad bets. Steve Staios – a salary dump – was acquired for a third round pick at the deadline was the cherry on top of a dubious sundae of bad moves that year.

The impetus to preserve the present and forever push to be a contender resulted in Sutter’s erratic efforts to get the Flames to the post-season in 2009-10. The choice to sell and reload for next year or buy and push for a playoff berth was never a choice in Sutter’s mind. The latter was the unquestioned goal, whatever the cost. The former was inconceivable.

The roster became bloated and cluttered with expensive flotsam in the aftermath of that season. Bad deals and no trade clauses littered the organization, from the newly acquired (Kotalik, Stajan, Hagman, Staios) to the slowly doddering (Cory Sarich). By the end, Sutter was basically buying up sand-bags to load into the back of a hopelessly stuck truck…only to see it sink even lower in the mud.

Conclusion

The Calgary Flames were a lost franchise when Darryl Sutter took the helm nearly a decade ago. A mix of his disdain for losing, his hockey acumen and some good luck combined to pull the organization out of the mire and make them both competitive and relevant for a fan-base desperate for some measure of success. His arrival was in-arguably a boon to the team.

As was his eventual firing. Sutter’s stature in Calgary grew to unwieldy proportions with the establishment of a monolithic Sutter-culture in the Flames front office; an edifice and echo chamber that at once shielded Darryl from criticism and reflected his own proclivities and vanities back to him. His vision became too narrowly focused in response, too captured by the goal of winning in the short-term and utterly blind to his own short-comings.

As a result, the Flames have returned from whence they came: facing an uncertain future with no readily apparent path back to contender status. Sutter breathed new life into the Calgary Flames upon his arrival. Flames fans can only hope his departure does the same.

Recent articles from Kent Wilson