Hitting, Shot Differentials and Variance

By Kent Wilson

11 years ago

A couple of things running through my head between Flames games today. The first topic has to do with hitting and winning versus shooting and winning. The second topic is on how advanced analysis in hockey is gaining prominence (but is still obviously misunderstood).

Outshoot rather than outhit

The NW division has become oddly enamored with tough guys and pugilists recently. The Flames traded for Brian McGrattan, the Cancuks claimed Tom Sestito and the Oilers acquired Mike Brown. This grinder parade was foreshadowed by Don Cherry a couple of weeks ago when he publicly praised the Leafs for deploying Colton Orr against the Rangers (the Leafs lost the game in question and were outshot handily by the way). Nevertheless, Toronto has gone a nice percentages based run in the last few weeks and now other decision makers (particularly of other mediocre teams) seem convinced that adding grit might be a quick fix solution for what ails them.

This has sparked a debate about the value of hits. Particularly versus the value of possession, since most of the guys in question get outshot at the best of times, even if they are limited to 4th line minutes.

Of course, there is a way to investigate such claims. Tyler Dellow looked at team hit rates and win rates in games from last season. The conclusion:

The data is, of course, hilarious. As a whole, teams did far better when they got outhit than they when they outhit the other side. I suspect that there are two main reasons for this: first, there probably is a great deal of truth to the argument that teams without the puck hit more, which doesn’t facilitate scoring. Second, there’s probably an element of teams that are behind deciding to focus on laying the body to try and turn the momentum – “Send out the energy line!” I suspect that what shows up here contains some score effects although, we know that trailing teams tend to possess the puck more, which would seem to give them less opportunity to hit.

Another stats-inclined Oiler fan, Michael Parkatti took a look at the correlation between hitting and things like shots for, shots against and points here. Again, nothing there:

not one r-square correlation was above 0.04, while most were below 0.01… meaning that less than 1% of the variability in shots or points could be explained by the variability in hits. The relationship is statistically random — some high hit teams are good, some are bad, and vice versa. There must be something else to explain why good teams are good?

Michael went the next step and did a regression analysis on shot differential and points. His findings in this case were the opposite – I can say with 99.9999999999985% confidence that there is a statistically significant positive relationship between shot differential and standings points.

Furthermore, the analysis allowed Michael to develop a regression equation for the relationship between points and shots, allowing us to forecast standings points for each team based on shots. The equation Standings Points = 91.68 + Shot Differential * 0.0275 where "shot differential" is a team’s total to date shots for-shots against. For the Flames, that comes out to 91.68 + (-7.8 * 0.0275) = 91.5 or about 92 points over a full season. Right in the 7-10 area they have settled in the last few years. By the way, for this truncated year that comes out to about 53 points – two points out of the assumed cut off of 55.

The point here isn’t to discount hitting or physicality altogether. Hockey is a tough game and contact can have it’s uses in certain circumstances, including separating a man from the puck, intimidating the opponent, etc. Of course, hitting can also have little-to-no-effect in most neutral situations and can actually be detrimental if a guy takes himself out of the play in order to hammer someone (a consistent Dion Phanuef failing during his time here).

The problem NHL decision makers seems to be the weighting of hitting and toughness beyond their utility. To be blunt, if you’re trading puck possession/outshooting for hitting/toughness, you’re almost certainly making your team worse, not better.

NHL Teams Interested in Stats! (but are still suspicious of them for the wrong reasons)

Yesterday, Elliotte Frieman published an interesting post on the recent Sloan conference (where NHLN contributor Eric T. presented his findings on zone entries). Friedman notes a handful of clubs attended the conference this year whereas it was just the Vancouver Cancuks four years ago (no, the Flames were not amongst them).

There’s a few bits on how teams are still secretive and proprietary with their own stats/models but still aren’t really sure if they have found anything paradigm shifting or truly useful. What stuck out to me, though, were some of the perceived strikes against statistical analysis presented in the piece.

First

One of the biggest issues with analytics is that its most hardcore followers tend to discount things like "heart" or "clutch performance" because they are not quantifiable.

Well, no, that’s not quite accurate. The issue with "heart" isn’t that it’s not quantifiable, strictly. We all know that humans vary in their degree of motivation, volition, passion, work ethic. Typically the reason I discount tales of "heart" and similarly fuzzy concepts is because they are too often marshaled in NHL analysis incorrectly: as the easy, go-to narrative when an outcome is extraordinary or unexpected.

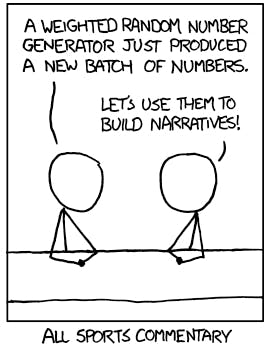

This tendency comes from years and years of sports reporters and decision makers mistaking natural variance in the game as true performance signals and, absent any other explanation, assigning blame or credit to some plausible personal psychological attributes of the team/players. I say this because ever since I began to track and understand percentages and regression to the mean in the NHL I’ve noticed that approximately 9/10 stories about a club’s lack of heart or incredible passion leading to losses or wins can be explained by low or high percentages. Whenever the percentages regress to the mean, wiping out the extraordinary results, so do the pop-psych articles in the MSM.

As an NHL coach or GM, I would certainly be cognizant of a given players commitment level to the team and to winning. However, I’d make sure to temper those considerations with the knowledge that I may mistake my liking a guy for his having a "good character" (subjectivity trap) and that our perception of a player’s performance and even underlying personality traits can be greatly influenced by results; results that are non-trivially dependent on things beyond that guy’s control.

As for clutch performance, it’s discounted because it is quantifiable and most have found that it doesn’t truly exist as a skill; ie something that can be reliably replicated or predicted. The perception of clutch is more or less the combination of some players simply being better than others + the natural ebb and flow of luck.

The issue in analytics isn’t merely assigning grades or blame after the fact – that’s the easy part. It’s finding metrics and models that help you predict outcomes with a certain degree of accuracy. As Gabriel Desjardins so eloquently put it "when people say that a team lacks the ‘intangibles’ to win, they are *making sh*t up* after the fact to match the results." The human tendency to see patterns in noise, to offer post-hoc rationlizations that neatly and easily explain events and to mistake hindsight for foresight means even honest attempts at analysis are beset by difficulties and pitfalls. That’s why doing this sort of work is an odd mixture of humility before the facts and endless skepticism.

Second

Oakland A’s general manager Billy Beane, the hero of Moneyball, blamed his team’s playoff failures on "luck." That’s a cop-out.

People who object to the term "luck" as used here don’t seem to understand what it means. The word comes with an unfortunate connotation of "not deserving" or "completely random". Outcomes in professional sports are weighted probabilities, not destinies, so it’s entirely possible for the better team to lose on any given night or even over a brief sample of games, like a best of seven series, for no other reason beyond variance. There are also other influences beyond the control of the players, coaches and GM’s of course: the officiating, injuries to key players, etc. Sports are interesting not only because of the action, competition and violence, but because they are a boiling cauldron of uncertainty. Sometimes the underdog wins. And sometimes it’s not because of any particular failing of the favorite.

I understand the reluctance amongst coaches and players to deploy "luck" as an explanation for wins or losses since it is completely unsastisfying to our sensibilities (and might be used as an excuse when things legitimately go wrong). However, the insistence that variance doesn’t really exist in the NHL and every outcome can be 100% explained by controllable factors causes people to fabricate stories and too often leads decision makers down the wrong path.

Recent articles from Kent Wilson