After Carolina game, Kris Versteeg lucky he wasn’t seriously injured

The Calgary Flames can consider themselves lucky to have only lost to Carolina by a score of 2-1 when the Hurricanes came to visit. Though the results of the game were less than desirable, one extremely fortunate outcome for the Flames was that Kris Versteeg was not badly injured.

Failed to load video.

I (Bill) did my undergrad in biomedical mechanical engineering, so I was intrigued by the aftermath of Versteeg’s injury. There was a few things regarding the biomechanics of the play that immediately grabbed my attention.

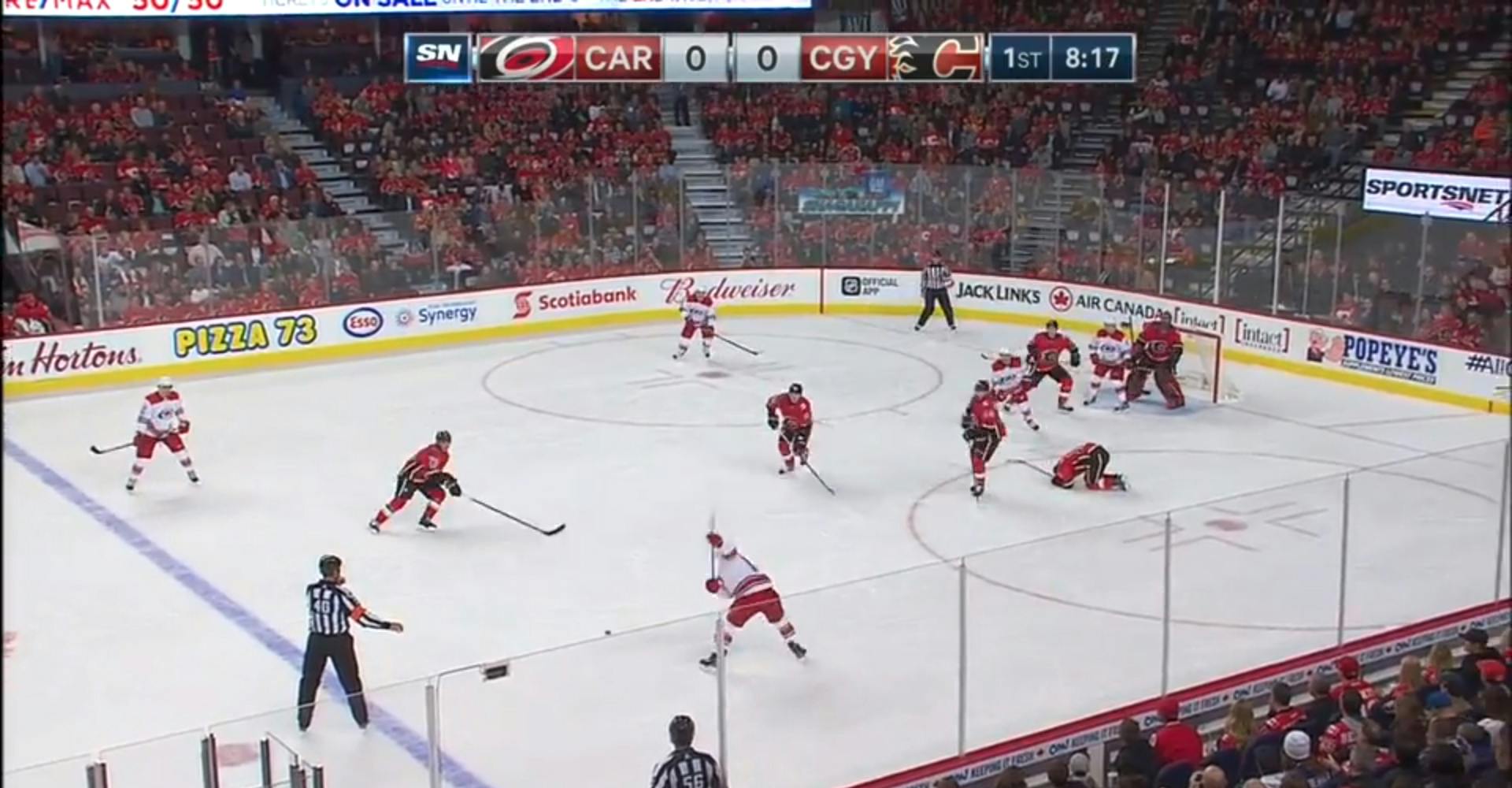

With 8:16 left to go in the first period, Jeff Skinner sent a one-timer from the point directly into the side of Versteeg’s head. This was a clear-cut example of what could go wrong when rules are followed too closely.

Portions of Rule 8.1 of the 2017-18 NHL Rulebook state:

When a player is injured so that he cannot continue play or go to his bench, the play shall not be stopped until the injured player’s team has secured control of the puck. If the player’s team is in control of the puck at the time of injury, play shall be stopped immediately unless his team is in a scoring position.

This rule makes an injured player extremely vulnerable as the play can continue indefinitely, effectively giving the opposing team a man advantage. However, the rule includes:

In the case where it is obvious that a player has sustained a serious injury, the Referee and/or Linesman may stop the play immediately.

Officially, Versteeg’s shift lasted 11 seconds. He spent at least eight of those seconds down on the ice, showing little attempt of getting up before Skinner took the shot. With all eyes trained on Versteeg writhing in pain, it was shocking that the whistle was not blown sooner. When anyone is down on the ice for that amount of time with the body language that Versteeg showed, it was definitely “obvious that [the] player has sustained a serious injury.”

As the play continued with Versteeg in the firing lane having little ability to protect himself, it became clear that not stopping the play was a collectively egregious decision by the referees and linesmen the moment the puck hit him. The incident was completely avoidable and in no way should an injured player ever receive a shot to his body, let alone his head, while he is down.

Though the way the play unfolded was upsetting, there might be insight gained that can prove a point, and potentially prevent these types of incidents from ever occurring again.

Two points worth discussing are what happened to the helmet and the likelihood of a concussion. Hockey helmets must pass regulations before they become available on the market. One thing to immediately address is that helmets are designed to protect a player by attenuating impact and inertial forces, and can not prevent concussions. They are rather robust and can take high impact forces before failing. However, an NHL calibre one-timer to a helmet can produce enough forces to cause a helmet to do exactly that:

The puck put a massive dent in the side of Versteeg’s helmet and cracked the outer shell. Despite the helmet looking worse for wear, the fact that it looked the way it did might have saved Versteeg from a serious injury. The helmet absorbed most of the impact, meaning Versteeg’s head did not.

The Win Column did a high-level engineering analysis to determine how much force a puck might exert upon impact, and showed that it was a lot higher than one might have expected. Assuming that the speed of Skinner’s one-timer was that of a typical NHL slapshot, say within the range of 100 miles per hour, it is no surprise that the helmet ended up like that. If Versteeg had also lost his helmet on the play, there is no telling how grave such an incident might have been.

When a puck hits a helmet, the padding inside will compress in a nonlinear fashion. In other words, the more the padding compresses, the more force is required to further compress it. The purpose of the compression is two-fold. It absorbs a lot of the impact energy and it also increases the amount of time taken for the head to stop moving.

This refers to how the head must stop moving in one direction before it can bounce off a surface into the reverse direction. An easy way to visualize this is to imagine dropping a bowling ball on hardwood compared to dropping it on a bed. When it is dropped on hardwood, it will immediately bounce, whereas it would sink into a bed and slow to a stop before bouncing back.

The same principle applies with a person’s head when they fall. In the case of taking a slapshot to the head, this can be seen as the extremely short amount of time the puck will compress the padding in the helmet before bouncing away. Believe it or not, the compression here completely alters the magnitude of the forces exerted onto the head, which in turn reduces the amount of acceleration experienced by the person’s head.

Much to everyone’s relief, Versteeg miraculously returned in the second period after passing concussion testing and being cleared to play. Combining concussion and sport often leads to controversy, especially when rushing a player to return. While seeing Versteeg back on the ice to finish the game was certainly reassuring that he was alright, one could not help but feel as though he might have still been nursing a head trauma without explicitly showing symptoms.

Experiencing that large of an impact to the head could obviously lead to either a concussion or some form of internal bleeding in the brain. With either injury, the symptoms could be subdued and could require further testing to verify, and it is definitely not possible to do so within the time frame given that Versteeg was back in the game no longer than an hour from being hit. It is definitely worth it to do proper due diligence to ensure that Versteeg will not have further issues.

One aspect that might have played a role in limiting the severity of the injury was that Versteeg had the spatial awareness to cradle his head as he was down on the ice. Given the movement that the head and neck can undergo upon impact, there are two types of accelerations that can occur: linear and rotational. The mechanisms behind concussions are extremely complex, but it is generally described as being caused by a rotational acceleration of the brain. This rotational acceleration could occur in various ways as the rotation of the head around the neck is largely uncontrolled.

Visualizing acceleration is rather complex as large magnitudes can be achieved in an infinitesimally small amount of time. Unlike velocity, which is visually discernible as a distance travelled over an amount of time, accelerations would not be as easily detectable within the contexts of a mid-game incident.

The rotational acceleration of the brain can result in shear forces, which are unaligned forces acting in opposite directions. With regards to brain injury, shear forces can cause damage to brain tissue, resulting in a concussion. With Versteeg cradling his head with his arms as he was hit by the puck, the impact and inertial forces might have transferred from the initial contact with the helmet into his right arm.

While this is purely speculative, this could be the reason why he was not diagnosed with a concussion. A lot of the rotational accelerations that could have resulted from a slapshot to the head was instead mitigated by the mere fact that his right arm was there to brace his head. Thanks to this, chances are the majority of the acceleration that Versteeg’s head underwent was linear and not rotational. If his arm was not there, the result could have been quite different, as his head could have been rapidly forced in one direction as a reaction to being hit by the puck, increasing the chances of a head trauma.

So far, it seems as though Versteeg is feeling alright, as he played over 17 minutes against Minnesota. He even scored a goal and looked quite like himself. If anything, the fact that he played a solid game two nights after such an incident shows how effective the helmet was in protecting him.

There is no doubt that taking a shot to the head the way Versteeg did was a completely preventable accident. The outcome of such an injury was extremely favourable as the alternatives could have been much more severe and harmful to his health. Versteeg was lucky that things happened the way they did, and we are thankful for that.

His awareness to protect himself might have saved him from a concussion and his helmet might have even saved his life. It just goes to show that putting player health and safety above all else should be paramount in the NHL, as Versteeg or any other player might not be so lucky next time.

Recent articles from Karim Kurji & Bill Tran