Notoriously Tricky Team Toughness

By Taylor McKee

6 years agoIn an article from The Hockey News’ 1993-94 yearbook, Brian Burke, fresh off his tenure as General Manager of the Hartford Whalers famously noted that: “Hockey is a man’s game and the team with the most men wins.” This quote, and a myriad of others from Burke you’re likely to see on the internet superimposed on images of pastoral frozen ponds, toothless men, hockey stick benches, identifies success on the ice with toughness.

This view is hardly unique, a cursory glance through the sports section of a Canadian bookstore is likely to supply an ocean of ink, oftentimes regaling readers of a bygone era when Men played the game. I could go on for several paragraphs about the linkage between hockey violence and the Canadian history but, alas, I will spare you the pedantry. The purpose of this article is to explore the Flames’ relationship with fighting, team toughness, and this upcoming season.

The Fightin’ Flames

Nov 16, 2016; Calgary, Alberta, CAN; Arizona Coyotes center Martin Hanzal (11) and Calgary Flames defenseman Brett Kulak (61) and defenseman Deryk Engelland (29) fight during the second period at Scotiabank Saddledome.

One of the most troubling aspects of the notion of ‘team toughness’ is the explicit connection made with fighting. But is this necessarily true? There is little doubt that the league has transitioned out of employing full-time NHL enforcers, though the Flames were (are) one of the last teams to move in that direction.

Though Calgary has employed some of the league’s most notorious fighters, in recent years it seems the trend has been to replace these fighters regularly. In three of the past four seasons, the player who led the Flames in fighting majors has not returned with the team the following year (check out the data from our friends at hockeyfights.com here) Furthermore, there is only one player from the 2013-14 season who recorded a fighting major still with the Flames – and it’s Mark Giordano who had one fight that season. Michael Ferland and Giordano are the only survivors from the 2014-15 season.

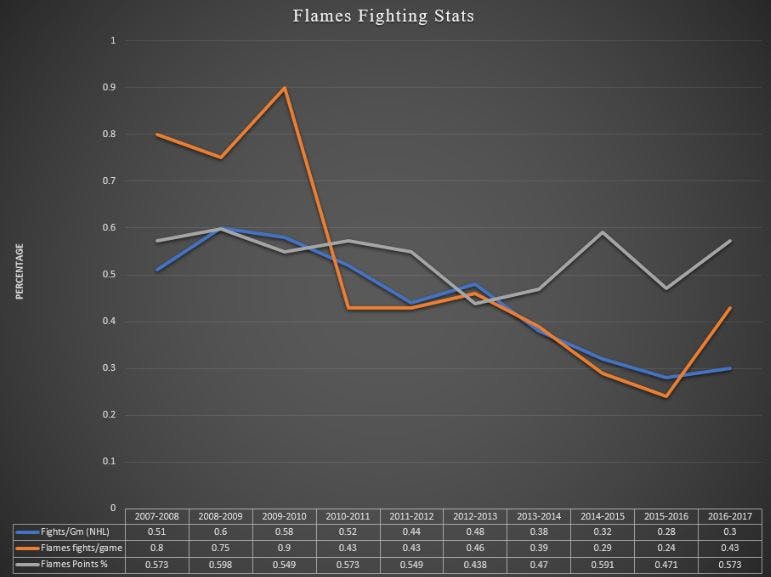

While that particular case is demonstrative of the massive roster overhaul that has occurred in Calgary during this period (and the fact that the 2013-14 Flames were garbage), it is indicative of a team’s priorities moving forward. To further illustrate how the Flames’ fighting statistics have fared over the past ten years of data. Here’s a look at the Flames fighting stats compared with the league average and, for fun, I threw in the Flames points %.

As you can see from the graph, during the first few years of declining fighting numbers in the NHL the Flames were bucking the trend until a sharp decline in 2010-11. From there, the Flames generally fought about the league average amount, until a (relatively surprising given my own recollection of last season) increase in 2016-17.

What does this mean, especially considering the points percentage factored in? I don’t think very much. Generally speaking, over the past 10 years the act of fighting and winning hockey games don’t seem to be related in any quantifiable way, though that discussion is surely not the purpose of this article. That being said, the public, and the media especially, place a great deal of emphasis on the relationship between a team’s perceived toughness and their willingness to fight.

Possibly Perfunctory Pugilism?

Failed to load video.

However, the relationship between fighting and ‘team toughness’ can be a confusing one, even for those who believe in the transformative effect of fisticuffs. For example, anthropomorphic textile disaster Don Cherry noted that: “This year, when they started off, everybody coming in thought McGrattan was going to play and they thought Bollig was going to play and they were afraid. All of a sudden it got around the league that ‘you don’t have to worry about Calgary anymore, they’re not tough anymore.”

You may recall that the 2014-15 season resulted in a first-round playoff victory for the “Earned Never Given” Bob Hartley-coached Flames. Cherry’s critiques are reinforced when you look at the fight data as well, the 2014-15 fight per game total is the second-lowest over the past 10 years. Though numerous critical deficiencies existed in the Hartley-era Flames, Hartley is credited with instilling ‘toughness’ and ‘hard-work’ into the Flames during this period, yet fighting didn’t seem to be a part of the team’s identity.

In January of 2017, following Johnny Gaudreau’s hand injury courtesy of Minnesota Wild stick-work, Calgary Herald columnist Eric Francis remarked that: ” The best way to help out the five-foot-nine winger is by putting a bigger premium on tough toughness – something this team still lacks despite Deryk Engelland’s best efforts.” Toughness, when extolled as a virtue for players like Engelland appears to market the idea of toughness divorced of context; fighting, in this case is promoted the pure unadulterated expression of a team’s ability to impose their physical will.

There, Francis notes that the Flames “lack toughness,” despite the fact that last year the Flames were among the league’s most prolific fighters. Most readers can recall moments where, over the past 10 seasons, the Flames felt tougher than their opponents or when an opponent was physically stronger than them. The real question becomes, what does ‘team toughness’ really mean, and does it have any relationship to fighting?

Team Toughness in 2017/18

Failed to load video.

The reason for this line of questioning is: NHL organizations seem to consistently equate fighting with toughness and bringing in a player with a long fight card adds to their ‘team toughness’ in the same way that losing a player detracts from it. This can lead to the perception that a team like the Flames is losing toughness when Deryk Engelland, Lance Bouma, and Brandon Bollig depart from the team and look to rectify it with other players (Luke Gadzic or Tanner Glass perhaps).

While it remains to be seen whether or not the newly acquired toughness will actually impact the Flames in any way, I do believe that a perceived lack of toughness led to their signings. My view is that players like Cody McLeod, Brandon Bollig, or Tanner Glass enhance the perception of toughness far more than a team’s actual ability to dictate play on the ice.

For something that is nearly impossible to define and essentially exists outside of any quantifiable metric, toughness remains an important part of hockey discourse. I suppose the central question posed by this article is: can a team be considered tough if they do not fight? I acknowledge that most readers will have different, nuanced answers to this question. In my estimation, players like Mark Giordano, Micheal Ferland, Travis Hamonic, and, to a lesser extent, Michael Stone provide something that Kent described as “Functional Toughness” which is a term I am very fond of, as it already implies that there can be toughness devoid of function.

Ultimately, deciding whether or not Tanner Glass, or someone like him, plays on the fourth line this season is not of paramount importance to the Flames. However, I think that the continued reluctance shown by the Flames to move on from an antiquated notion of what makes a team ‘tough’ will limit their ability to utilize their depth effectively. Let me know what you think, does a team need to fight prolifically to be considered tough?

Recent articles from Taylor McKee