Special Teams Science: Zone Entries Against at 4v5

By Mike Pfeil

5 years agoA couple weeks back we took a very brief and high-level look at how the Calgary Flames approached entering the zone on the man advantage. There was no surprise at the time that, well, they were hot and cold. After all, that’s been the calling card of the Flames’ special teams for over a year now.

When it comes to the penalty kill, it’s similarly an interesting bag of results.

One positive, when we looked very early on at the Flames’ forecheck approach under Ryan Huska, was a trend in terms of suppressing zone entries against where the opposing puck carrier had possession. This was a hurdle the Flames simply struggled with through the majority of last season.

Digging into how the Flames defend their blue line against an opposing team’s breakout yields some interesting results when we visualize a portion of the tracking work I’ve done this season. For this exercise we’ll use what data I have tracked (12 games so far), the forechecking formation utilized, and the essential vitals to how they’re looking early on as we fast approach the quarter mark of the season.

Let’s start by evaluating the overall results and then dissect it by some of the key areas of interest:

One of the more intriguing elements is how the Flames have stepped up on breaking up entries – be it actively or passively intervening or forcing the puck carrier offside – before the blue line. When entries are being broken up it’s much more than utilizing an active stick or applying direct pressure, but utilizing positioning (their own, or the power play’s against them) to take away a path to entering the zone.

In some cases, the entry is broke up after they cross the line, but the team as a whole has been active at or before the blue line:

Failed to load video.

- In the first sequence, Sam Bennett functions as the ‘F1’ using time, space, and his body to disrupt the drop-pass play to David Krecji, forcing the turnover and broken up entry. All three remaining PKs are spaced appropriately, with room to adjust as the play was breaking out.

- In the second sequence, the Flames work the drop-pass play by forcing Nashville into a situation where they lose possession. The pincer movement of Mark Jankowski and Mark Giordano are the stars in this sequence, allowing for a recovery of the loose puck and clearing of the puck.

- For the third sequence, new Flame Derek Ryan plays the role of the F1, applying indirect pressure to Ryan Ellis as he breaks in through the middle of the ice. The Flames’ defenders all activate around the play as there isn’t any room for Ellis and Viktor Arvidsson, breaking up the play and eating more time off the clock.

This final zone entry breakup is a prime example of how the Flames can use effective skating and passive pressure to funnel the puck carrier into the preferred outcome for the PK:

Failed to load video.

With Backlund acting as the F1 in the formation, the Flames well aware of the time management situation in front of them. Backlund stays with the play, maintaining position in an opportune area while keeping an eye on where both trailing Predators are. A bit of luck breaks up the cross-ice pass and forces the Predators to regroup partially.

Again, Backlund shadowing Roman Josi functions as the F1, funnelling him directly into Noah Hanifin forcing the turnover and the failed entry. Though they eventually get the third and final entry, Nashville doesn’t create much as there is only seconds left on the power play.

Efficient use of time combined with effective positioning and attention to detail are all on display here.

Formation Specifics: Passive 1-3

Shifting to how where the opposition is entering the zone, there’s a curious case to explore about why the entry locations are often clustered together. For attacking teams, the Flames often employ the Passive 1-3 as their default forecheck formation. Of the 95 instances where the Flames have been in some discernible forecheck formation, they’ve employed the Passive 1-3 69 times (72.63%).

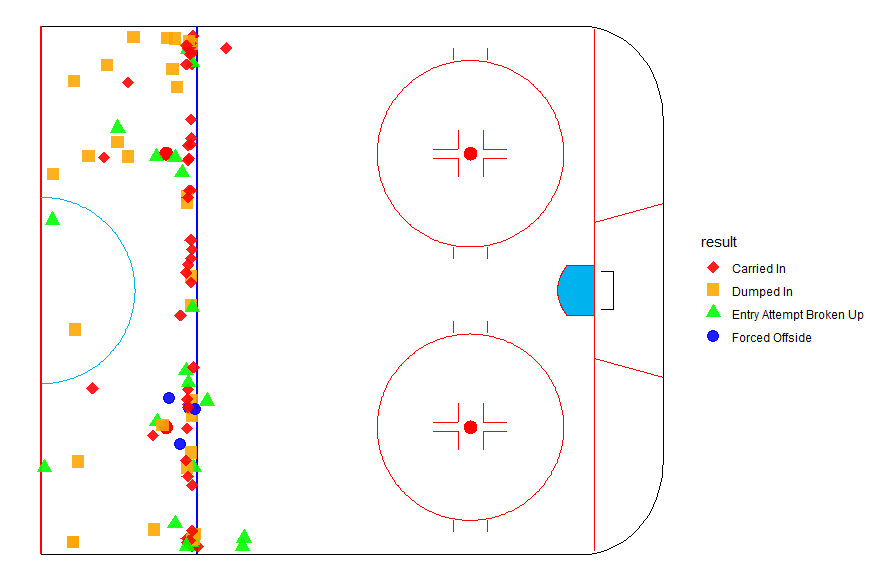

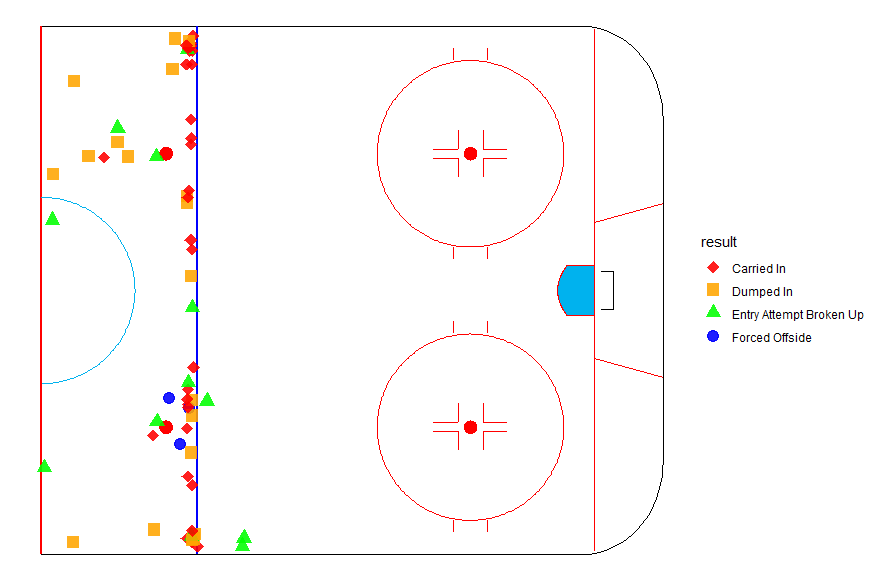

While it’s nice that they’ve settled into a default that gives them options with how the attacking power play is breaking out, we still need to get an idea if the Flames are deploying it as intended. So let’s look at how the Passive 1-3 formation looks when plotted out:

We can see that there aren’t many entry options breaking down the middle of the ice because of how the formation is designed to limit breakouts through the middle of the ice. For the Flames, what we’re seeing is a lot of entries and entry attempts happening where there are seams in the formation. This isn’t ideal, but it’s worth exploring in greater detail.

Teams are capitalizing on a few areas that might be impacted by the lack of lateral movement as the remaining three penalty killers that make up the Maginot Line of sorts:

Failed to load video.

In the first sequence, the Flames aren’t in a properly set up Passive 1-3 as it becomes quickly evident that the Washington Capitals are going to easily gain the zone. A quick pass wide to Evgeny Kuznetsov catches Backlund off guard, forcing Elias Lindholm to get into a race back into position (it almost becomes a sad excuse for a Same Side Press): all of which culminates with an easily acquired lane for Kuznetsov to enter the zone and allow the Capitals to get configured.

Failed to load video.

In the blowout against the Pittsburgh Penguins, the Flames are caught with a clever drop-pass to the trailer. The problem here is the waiting game played by the Pens as by the time Evgeni Malkin appears and gains possession of the puck, Travis Hamonic has sagged all the way back to the high slot leaving a lane between F1, Jankowski and Giordano to open up.

Though out of frame, the Penguins have additional options for touch-up passes if they wanted to create a different type of entry, but it’s hard to disagree with letting Malkin enter the zone at full speed.

Failed to load video.

Finally, most recently against the Toronto Maple Leafs, the Flames get caught with a very clever play that exploits the Passive 1-3 with a combination of a drop pass and using Morgan Rielly to obstruct Garnet Hathaway from pinching on Mitch Marner. Rielly starts the breakout but drops to Marner as the gap between Rielly and Hathaway is at its most critical. This prevents Hathaway and immediately puts him at risk of an interference call if played poorly. This also obfuscates TJ Brodie and Giordano’s view, forcing focus on Marner while John Tavares waits for the touch-up pass to enter the zone.

A big ask can be made on whether or not Huska and Bill Peters can have their aforementioned Maginot Line play with a little more lateral movement, attention to managing the gap between the puck carrier, and active stick work from the line of penalty killers. Finding small ways to create a bit more obstruction on the entry attempt can be a boon to the play occurring.

Objectively the goal shouldn’t be about preventing any and every entry, but working to the most preferred outcome. If the preferred outcome (broken up entry, offside, or turnover) isn’t achieved, there should be a plan ‘B’ in place (aim for a dumped in entry). We know from data presented last season and through part of this season that in general there are fewer shots generated from a dumped in entry versus a controlled entry.

| Entry type | Shots per entry | Unblocked shots per entry |

| Controlled | 0.51 | 0.68 |

| Dumped in | 0.22 | 0.36 |

Retreating Box usage

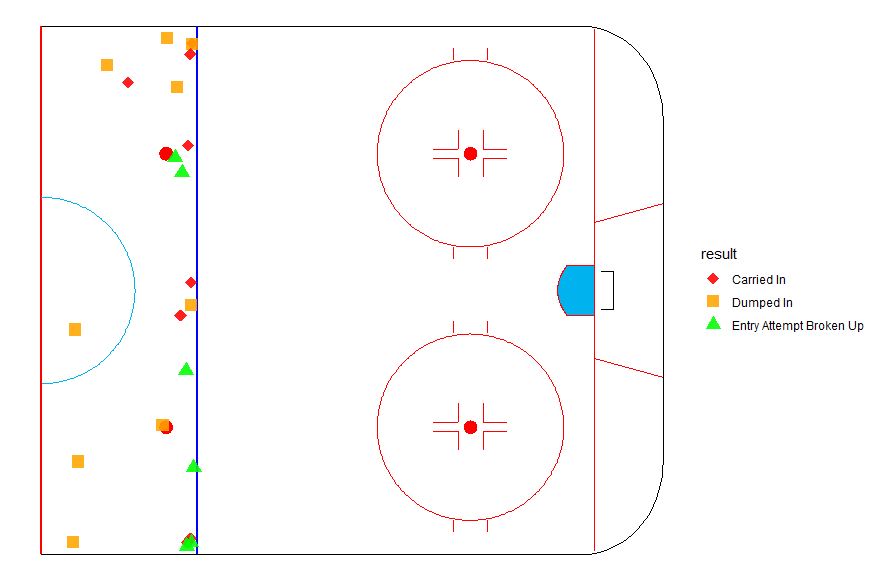

One thing to keep an eye on as the season progresses and the sample sizes increase is how the Flames’ use of the Retreating Box looks. Early on, with only a mere 24 deployments, the Flames have seemingly managed to limit the number of entry attempts through the middle of the ice in this forechecking approach:

Most recently the Flames deployed this forecheck four times against the Capitals to some success (50% breakup rate). In game four, versus the St. Louis Blues, the Flames maximized its benefits by deploying it nine times and forcing the Blues to dump the puck in four times (44.44%); on top of that they were successful in breaking up three entries, too.

Why this matters and moving ahead

Again, to sound like a broken record, there continues to be very limited work in this field and the game desperately needs it. Finding efficiencies on ice in how a team can maximize their time while playing shorthanded – or while on the man advantage – is what the game has been brought to. For the Flames, it’s a make or break year for a lot of reasons, and the special teams are one of them.

The Pacific division is, well, trash at this point. In order for the Flames to separate themselves from their Pacific brethren and become the team a lot of fans believe they can be they need to fine tune everything before Christmas. The opportunities for improvement extend beyond just simple systemic tweaks, and within the players themselves. We’ve started to see new-look PK units (Backlund and Lindholm) come together, which was a predicted outcome from some offseason work I explored on Lindholm during his tenure in Carolina.

Ultimately, if the Flames can uncover and master some fabled secret in a particular forecheck formation or strategy they might as well do it as soon as possible to reap the rewards. Teams are smart and they’ll figure it out before it’s too late. Let’s just hope the Flames can be quicker and smarter than the rest.

Editorial note: Special thanks in no specific order as all have been vital to helping this project run: Luke and Josh from Evolving-Hockey (coding assistance), C. Tompkins (coding assistance), Ryan Stimson (guidance and insights), and Prashanth Iyer (coding and theorycrafting).

Recent articles from Mike Pfeil